Arjun Yadav

Linear algebra in ~10 minutes

Aug 31, 2022

Note: This post was last edited on Sep 05, 2022.

I recently finished a linear algebra course, which was targeted toward people wanting to learn the maths behind machine learning. Here's a summary of what I've learned.

What is Linear Algebra?

In simple terms, linear algebra is the maths behind transformations, vectors and matrices. It can be thought of as an extension of the Cartesian geometry that we all are (hopefully!) familiar with.

However, it's not just about geometry. Linear algebra is a really powerful tool when it comes to analysing and solving problems with data, something we'll be looking at later in this post.

Vectors

A vector looks like this \( \begin{bmatrix} a_{1} \\ a_{2} \\ \vdots \\ a_{m} \end{bmatrix} \) (column vector) or like this \( \begin{bmatrix} a_1 \ a_2 \ \cdots \ a_{m} \end{bmatrix} \) (row vector). They can contain any numerical quantity.

We could, for example, represent the number of votes that each ice cream flavour gets with a vector:

\[ \begin{bmatrix} 102 \rightarrow \text{Chocolate} \\ 58 \rightarrow \text{Cookies and Cream} \\ 128 \rightarrow \text{Vanilla} \\ 34 \rightarrow \text{Red Velvet} \\ 1 \rightarrow \text{Taco Seasoning} \\ \end{bmatrix} \]

Matrices

A matrix can be thought of as many column/row vectors merged to make an \(m \times n\) matrix:

\[ \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} & a_{12} & a_{1n} \\ a_{21} & a_{22} & a_{2n} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots \\ a_{m1} & a_{m2} & a_{mn} \\ \end{bmatrix} \]

The \(a_{21}\) tells us that this is the element in \(2^{\text{nd}}\) and \(1^{\text{st}}\) column of the matrix.

Matrices could help in, say, representing an image as numbers, as shown in this MNIST example:

In the above example: the darker the pixel is, the closer it gets to 1.

Operations

Vectors

Adding, subtracting and multiplying vectors by a scalar[1] is pretty straightforward (so long as all the vectors involved are of the same dimension):

\[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 3 \\ 5 \\ 7 \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 2 \\ 4 \\ 6 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 5 \\ 9 \\ 13 \end{bmatrix} \]

\[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 3 \\ 5 \\ 7 \end{bmatrix} - \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 2 \\ 4 \\ 6 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} \]

\[ 2 \times \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 3 \\ 5 \\ 7 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 2 \\ 6 \\ 10 \\ 14 \end{bmatrix} \]

We can also take the dot/inner product of vectors of the same dimension (which results in a scalar):

\[ \begin{bmatrix} a_{1} \\ a_{2} \\ a_{3} \\ a_{4} \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} b_{1} \\ b_{2} \\ b_{3} \\ 2_{4} \end{bmatrix} = a_{1}b_{1} + a_{2}b_{2} + a_{3}b_{3} + a_{4}b_{4} \]

Matrices

Adding and subtracting matrices of the same dimension is very similar to adding and subtracting vectors:

\[ \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} & a_{12} \\ a_{21} & a_{22} \\ \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} b_{11} & b_{12} \\ b_{21} & b_{22} \\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} + b_{11} & a_{12} + b_{12} \\ a_{21} + b_{21} & a_{22} + b_{22} \\ \end{bmatrix} \]

\[ \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} & a_{12} \\ a_{21} & a_{22} \\ \end{bmatrix} - \begin{bmatrix} b_{11} & b_{12} \\ b_{21} & b_{22} \\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} - b_{11} & a_{12} - b_{12} \\ a_{21} - b_{21} & a_{22} - b_{22} \\ \end{bmatrix} \]

To multiply two matrices, we take the dot product of all the rows of the first matrix with all the columns of the second matrix:

- We can only do this if the dimensions are \(n \times m\) and \(m \times p\), meaning the number of columns of the first matrix must equal the number of rows of the second matrix.

- The result will be a matrix of dimensions \(n \times p\).

- Matrix multiplication is NOT commutative, which means that \(A \times B \) does not always equal \(B \times A\).

- Lastly, this process works for matrix and vector multiplication as well.

\[ \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} & a_{12} & a_{13} \\ a_{21} & a_{22} & a_{23} \\ a_{31} & a_{32} & a_{33} \\ \end{bmatrix} \times \begin{bmatrix} b_{11} & b_{12} & b_{13} \\ b_{21} & b_{22} & b_{23} \\ b_{31} & b_{32} & b_{33} \\ \end{bmatrix} = \]

\[ \begin{bmatrix} a_{11}b_{11}+a_{12}b_{21}+a_{13}b_{31} & a_{11}b_{12}+a_{12}b_{22}+a_{13}b_{32} & a_{11}b_{13}+a_{12}b_{23}+a_{13}b_{33} \\ a_{21}b_{11}+a_{22}b_{21}+a_{23}b_{31} & a_{21}b_{12}+a_{22}b_{22}+a_{23}b_{32} & a_{21}b_{13}+a_{22}b_{23}+a_{23}b_{33} \\ a_{31}b_{11}+a_{32}b_{21}+a_{33}b_{31} & a_{31}b_{12}+a_{32}b_{22}+a_{33}b_{32} & a_{31}b_{13}+a_{32}b_{23}+a_{33}b_{33} \\ \end{bmatrix} \]

Closer look at vectors

Geometric depiction and basis vectors

Vectors can also be represented geometrically. To do this, we use two unit vectors as our basis vectors, these are called \(i\) (x-axis) and \(j\) (y-axis) in the 2D case.

Each vector is made up of \(x\) and \(y\) components. So the \(i\) basis vector \(= \begin{bmatrix} 1 \rightarrow x \\ 0 \rightarrow y \\ \end{bmatrix} \) and the \(j\) basis vector \(= \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \\ \end{bmatrix} \)

That means we can represent vectors geometrically in one of two ways:

- Splitting it into its components, \(\vec{a} = \begin{bmatrix} 2 \\ 3 \\ \end{bmatrix} \)

- Using the unit vectors, \(\vec{a} = 2i+3j\)

Both result in the following diagram:

This also means that we can represent vector operations geometrically. We add vector tip-to-tail:

A scalar product means repeating a vector as many times as the magnitude of the scalar. If the scalar is negative, we flip the vector's direction:

Finally, subtracting vectors is simply adding a negative:

The last thing to note is the modulus of a vector, which is simply the distance of the vector from the origin. Using the Pythagorean theorem:

\[|ai+bj| = \sqrt{a^2+b^2}\]

Dot product generalization

What happens if we dot[2] a vector \(\vec{r} = \begin{bmatrix} a \\ b \\ \end{bmatrix} \) with itself?

\[ \vec{r} \cdot \vec{r} = a \cdot a + b \cdot b \]

This means that, \(\vec{r} \cdot \vec{r} = |r|^2\). We'll be using this result soon.

Now, if we construct two vectors \(\vec{r}\) and \(\vec{s}\) and join them tail-to-tail to subtract them, we get a resulting vector \(\vec{r} - \vec{s}\).

We can use the Cosine rule, which says that \(c^2=a^2+b^2-2ab\cos\theta\), where \(\theta\) is the angle between \(a\) and \(b\), and \(c\) is the side opposite to \(\theta\).

Doing some substitution with the modulus function to get only the magnitude of the vectors:

\[|r-s|^2 = |r|^2+|s|^2-2|r||s|\cos\theta\]

Now, we can use \(\vec{r} \cdot \vec{r} = |r|^2\) to say that

\[|r-s|^2 = (r-s) \cdot (r-s)\]

Expanding the right-hand side,

\[|r-s|^2=|r|^2+|s|^2-2r \cdot s\]

Which means, \[|r|^2+|s|^2-2r \cdot s = |r|^2+|s|^2-2|r||s| \cos\theta\]

Doing some algebraic manipulation, we get our generalization for the dot product! \[r \cdot s = |r||s|\cos\theta\]

We call \(|s|\cos\theta\) the projection, which you can think of as the shadow of \(s\) on to \(r\).

\[\text{Projection} = |s|\cos\theta = \frac{r \cdot s}{|r|}\]

The problem with the above definition for projection is that it doesn't give us any sense of direction. For that, we can say

\[\text{Vector projection} = r\frac{r\cdot s}{r \cdot r} \text{ or } r\frac{r\cdot s}{|r|^2} \]

Last thing, notice that when \(\theta = 0^{\circ}\), \(r \cdot s = |r||s|\) (since \(\cos 0^{\circ} = 1\)). Similarly, when \(\theta = 90^{\circ}\), \(r \cdot s = 0\) (since \(\cos 90^{\circ} = 0\)) and when \(\theta = 180^{\circ}\), \(r \cdot s = -|r||s|\) (since \(\cos 180^{\circ} = -1\))

Closer look at matrices

Transformations and changing basis

Vectors aren't tied to their basis vectors. The transformation matrix to transform basis vectors \(i\) and \(j\) to \( \begin{bmatrix} x \\ y \\ \end{bmatrix} \) and \( \begin{bmatrix} a \\ b \\ \end{bmatrix} \) is \( \begin{bmatrix} x & a \\ y & b \\ \end{bmatrix} \).

With this knowledge, we can get into some common types of transforms:

- Identity (an \(n \times n\) matrix with 1's on the leading diagonal[3] and zeros everywhere, it does nothing to a vector/matrix on multiplying, we can also use negatives here for mirrors along the axes): \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix} \times \begin{bmatrix} x \\ y \\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} x \\ y \\ \end{bmatrix} \]

- Scale (an identity matrix where instead of 1s on the leading diagonal, we have \(a, b, ...\) to scale \(x\) by \(a\), \(y\) by \(b\) and so on, we can also use negatives here for inversion): \[ \begin{bmatrix} a & 0 \\ 0 & b \\ \end{bmatrix} \times \begin{bmatrix} x \\ y \\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} ax \\ by \\ \end{bmatrix} \]

- Shear (combination of keeping at least one component the same and scaling at least one compoennt): \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & a \\ 0 & b \\ \end{bmatrix} \text{ or } \begin{bmatrix} a & 1 \\ b & 0 \\ \end{bmatrix} \]

- Rotation (general form for any \(\theta\)): \[ \begin{bmatrix} \cos\theta & \sin\theta \\ -\sin\theta & \cos\theta \\ \end{bmatrix} \]

Determinants, Inverses and Transposes

The determinant of a matrix is a scalar property of a matrix, and it's useful for calculating the inverse of a matrix (which we'll get to).

For a \(2 \times 2\) matrix \(A = \begin{bmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \\ \end{bmatrix} \), the determinant (\(|A|\)) is \(ad-bc\). Determinants are complicated to calculate outside of \(2 \times 2\) matrices.

The inverse of a matrix/matrix inverse is a matrix \(A^{-1}\) such that \(AA^{-1} = I \text{ }\) (\(I\) being the identity matrix,\( \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix} \)).

For a \(2 \times 2\) matrix \( \begin{bmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \\ \end{bmatrix} \), the inverse is \( \frac{1}{ad-bc} \begin{bmatrix} d & -b \\ -c & a \\ \end{bmatrix} \), Inverses are complicated to calculate outside of \(2 \times 2\) matrices.

Finally, the transpose of a matrix (\(A^T\)) simply involves converting every row of \(A\) to a column:

\[ \begin{bmatrix} a & b & c \\ d & e & f \\ \end{bmatrix} \rightarrow \begin{bmatrix} a & d \\ b & e \\ c & f \end{bmatrix} \]

Gaussian elimination and Row echelon form

Let's apply what we've learned to solve a problem.

Say we had to solve some simultaneous equations: we know that 5 apples, 6 bananas and 8 coconuts cost us \(\$24.77\), 2 apples, 10 bananas and 7 coconuts cost us \(\$20.13\) and 6 apples, 4 bananas and 10 coconuts cost us \(\$29.44\). How much does each apple (\(a\)), banana (\(b\)) and coconut cost (\(c\))?

We can represent this as matrix times a vector:

\[ \begin{bmatrix} 5 & 6 & 8 \\ 2 & 10 & 7 \\ 6 & 4 & 10 \end{bmatrix} \times \begin{bmatrix} a \\ b \\ c \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 24.77 \\ 20.13 \\ 29.44 \end{bmatrix} \]

To solve this, we have to convert our matrix to row echelon form: where the numbers below the leading diagonal are 0s. More specifically, we would also like for the leading diagonal to be 1s (this is called reduced row echelon form). For us, this is a bit of trial-and-error, where we multiply and subtract rows from each other (I used a calculator, though this can be easily done without steps with SymPy or NumPy):

- \(R_1 \leftarrow \frac{R_1}{5}\): \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1.2 & 1.6 \\ 2 & 10 & 7 \\ 6 & 4 & 10 \end{bmatrix} \times \begin{bmatrix} a \\ b \\ c \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 4.954 \\ 20.13 \\ 29.44 \end{bmatrix} \]

- \(R_2 \leftarrow R_2 - 2R_1\) \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1.2 & 1.6 \\ 0 & 7.6 & 3.8 \\ 6 & 4 & 10 \end{bmatrix} \times \begin{bmatrix} a \\ b \\ c \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 4.954 \\ 9.592 \\ 29.44 \end{bmatrix} \]

- \(R_3 \leftarrow R_3 - 6R_1\) \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1.2 & 1.6 \\ 0 & 7.6 & 3.8 \\ 0 & -3.2 & 0.4 \end{bmatrix} \times \begin{bmatrix} a \\ b \\ c \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 4.954 \\ 9.592 \\ -0.284 \end{bmatrix} \]

- \(R_2 \leftarrow R_2 - \frac{5}{38} \cdot R_2\) \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1.2 & 1.6 \\ 0 & 1 & 0.5 \\ 0 & -3.2 & 0.4 \end{bmatrix} \times \begin{bmatrix} a \\ b \\ c \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 4.954 \\ 1.26210529 \\ -0.284 \end{bmatrix} \]

- \(R_1 \leftarrow R_1 - \frac{6}{5} \cdot R_2\) \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 1 & 0.5 \\ 0 & -3.2 & 0.4 \end{bmatrix} \times \begin{bmatrix} a \\ b \\ c \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 3.43947365 \\ 1.26210529 \\ -0.284 \end{bmatrix} \]

- \(R_3 \leftarrow R_3 + \frac{16}{5} \cdot R_2\) \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 1 & 0.5 \\ 0 & 0 & 2 \end{bmatrix} \times \begin{bmatrix} a \\ b \\ c \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 3.43947365 \\ 1.26210529 \\ 3.75473693 \end{bmatrix} \]

- \(R_3 \leftarrow \frac{R_3}{2}\) \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 1 & 0.5 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \times \begin{bmatrix} a \\ b \\ c \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 3.43947365 \\ 1.26210529 \\ 1.87736846 \end{bmatrix} \]

- \(R_1 \leftarrow R_1 - R_3\) \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0.5 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \times \begin{bmatrix} a \\ b \\ c \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1.56210519 \\ 1.26210529 \\ 1.87736846 \end{bmatrix} \]

- \(R_2 \leftarrow R_2 - \frac{1}{2} \cdot R_3\) \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \times \begin{bmatrix} a \\ b \\ c \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1.56210519 \\ 0.32342106 \\ 1.87736846 \end{bmatrix} \]

Thus, \(a=\$1.56210519\), \(b = \$0.32342106\) and \(c = \$1.87736846\).

Orthonormal matrices and the Gram-Schmidt process

We like our matrices to be orthonormal, which is where the constituent vectors are \(90^{\circ}\) to each other since the determinant is \(±1\) and \(A^{T}A=I\).

Assuming the vectors are linearly independent[4], we can use the Gram-Schmidt process to convert a matrix to an orthonormal one:

- Take \(V_1\) from the matrix and set \(e_1 = \frac{V_1}{|V_1|}\) (this is called normalizing the vector)

- Now we set a "temporary vector" \(U_2 = V_2 - (V_2 \cdot e_1) \cdot \frac{e_1}{|e_1|}\). Notice that \(|e_1| = 1\). Thus, \(U_2 = V_2 - (V_2 \cdot e_1) \cdot e_1\) and \(e_2 = \frac{U_2}{|U_2|}\).

- Then, \(U_3 = V_3 - (V_3 \cdot e_1) \cdot e_1 - (V_3 \cdot e_2) \cdot e_2\) and \(e_3 = \frac{U_3}{|U_3|}\)

- Thus, after \(e_1\), we can generalize \(e_n = \frac{U_n}{|U_n|}\), where \(U_n = V_n - (\sum_{i=1}^{n-1} (V_n \cdot e_i) \cdot e_i)\)

Collecting all the \(e_n\) gives us our orthonormal matrix!

Eigenvectors and Eigenvalues

Eigenvectors are the vectors that are characteristic of a transform. Once a transform is applied to a set of vectors, the eigenvectors are only transformed by a scalar number (called the eigenvalue) after a transformation matrix is applied.

For example, on applying the transformation matrix \( \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 0 \\ 0 & 2 \\ \end{bmatrix} \) to a set of unit vectors + the diagonal vector in between them, we see that the horizontal and vertical vectors are characteristic to the transformation matrix (with an eigenvalue of 2), while the diagonal vector isn't (since its direction has changed).

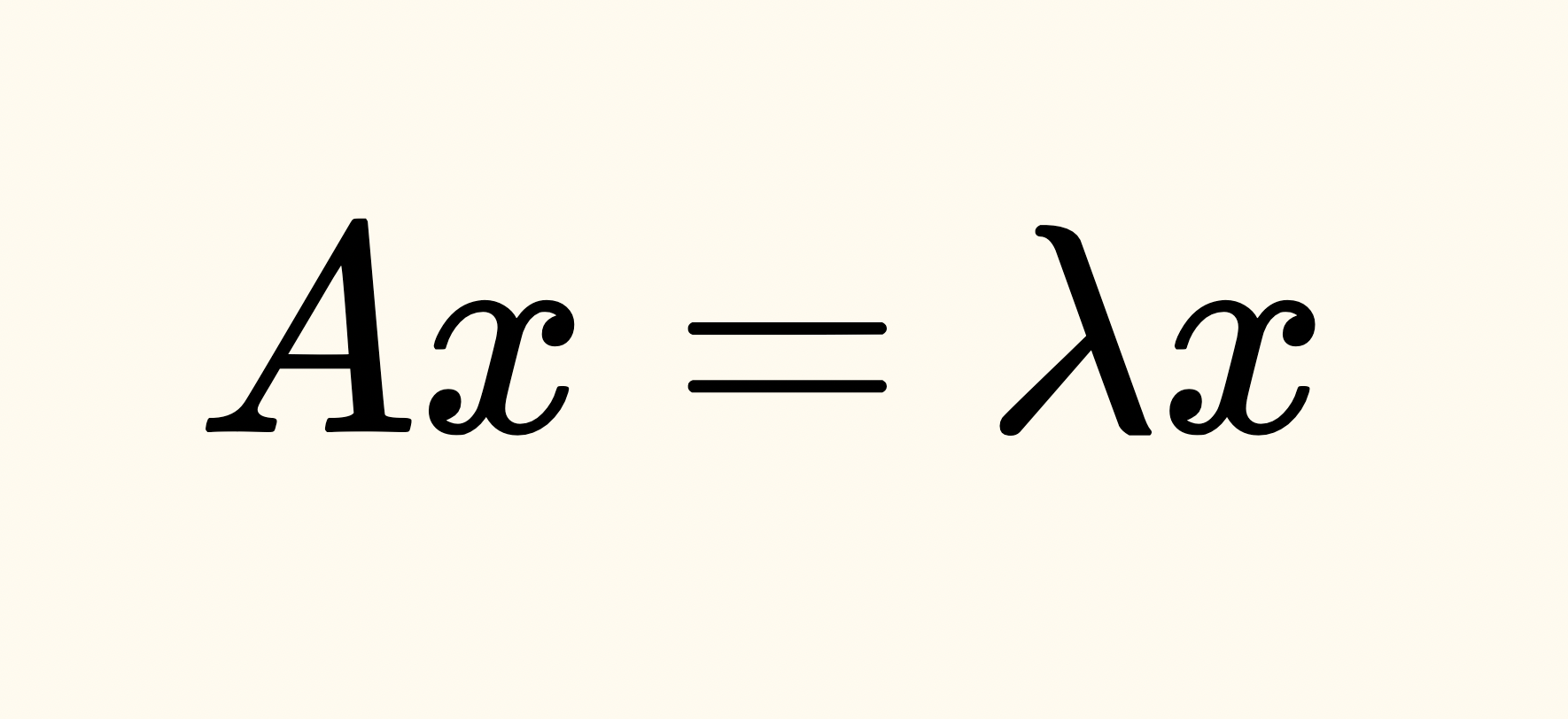

Geometrically finding all eigenvectors can become difficult. To overcome this, we use the definition of an eigenvector \(x\):

\[Ax = \lambda x\]

Where \(A\) is our transformation matrix and \(\lambda\) is the eigenvalue. This also means that \((A-\lambda I)x = 0\) (notice that we introduce the identity matrix \(I\) since we can't subtract a scalar from a matrix).

Finally, to find such eigenvalues (and hence eigenvectors by plugging in \(\lambda\) in to \((A-\lambda I)x=0\)), we use the characteristic polynomial which is, for a \(2 \times 2\) transformation matrix \(A = \begin{bmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \\ \end{bmatrix} \):

\[\lambda^{2}-(a+d)\lambda + ad-bc =0\]

PageRank

To tie up what we've learnt in this post, let's look at an application that surprisingly uses eigentheory.

Ranking the webpages on the internet based on of how well connected they are is vitally important to search engines, such as Google (whose very own founders developed PageRank)

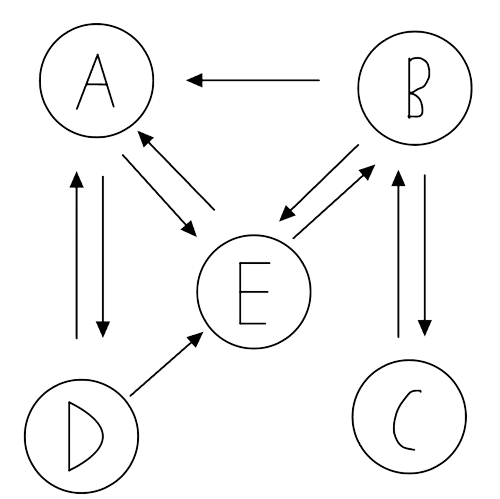

Say we had five pages connected like this:

We can say that the probability vector for webpage A being clicked from web pages A, B, C, D and E are:

\[L_A = \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 0.\bar{3} \\ 0 \\ 0.\bar{3} \\ 0.\bar{3} \end{bmatrix} \]

We construct a probability square matrix \(L\) by joining \(L_A, L_B, ..., L_E \):

\[L = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0.\bar{3} \\ 0.\bar{3} & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0.\bar{3} \\ 0 & 0.5 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0.\bar{3} & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0.\bar{3} \\ 0.\bar{3} & 0.5 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \]

To rank these websites, we start with a rank vector that assigns equal probabilities initially:

\[r = \begin{bmatrix} 0.2 \\ 0.2 \\ 0.2 \\ 0.2 \\ 0.2 \\ \end{bmatrix} \]

And we learn the ranks iteratively, where \(r^{i+1} = Lr^{i}\). One more thing that we can consider is a damping factor, which is the probability between \(0\) and \(1\) of a user doing something other than clicking a hyperlink:

\[r^{i+1} = d \cdot Lr^{i} + \frac{1-d}{n} \]

Using some simple NumPy code with a damping factor of \(0.25\) we get the following ranks:

1. B

2. A

3. E

4. D

5. C

A scalar is a numerical quantity with only magnitude and no direction. Integers are typically what we mean when we talk about scalars in this context. ↩︎

Shorter way to say "dot product" or "take the dot product". ↩︎

Means the diagonal from the top-left corner to the bottom-right corner. ↩︎

None of the vectors can be written as a scalar multiple of another vector. ↩︎